Hero Worship

The ancient Greek hero is the pinnacle of success and arete (prowess): one whose actions reverberate through the centuries and whose power can influence the world even after death. These powerful, superhuman figures were extremely important in Greek life, holding great significance in political, social, and religious life. Heroes were used to help explain the way the world was, teach lessons, and explore themes of tragedy and virtue. Heroes were frequently depicted in works of art (first cropping up in a recognizable way in the Geometric period) that ranged from common painted pots to lavish sculpture programs, indicating their importance to all social strata in Greek society.

The origins of hero worship are murky but, as J.N. Coldstream (1976) suggests, it most likely was born out of a combination of long-standing ancestor worship and the proliferation of the Homeric canon. Hugh Sackett’s own work helps explore this because of his contributions as co-excavator of the Toumba cemetery in Lefkandi, a site which boasts one of the most impressive tombs from the proto-Geometric period (roughly 1030 to 900 BCE), including a tumulus filled with the remains of four horses, a woman sporting expensive jewelry, and a man outfitted with the wares of a warrior.

Cult activities often centered around the tomb of a fallen hero, the Greeks believing that their power was most concentrated around their remains. Most heroes were treated as distinct from most of the Olympian gods, their worship often driven by small, local groups that dedicated their offerings as libations rather than burning food near and outdoor altar. However, others, such as Theseus, were transformed into personifications of the polis and worshipped in large, city-wide festivals. The Greek relationship with heroes varied over space and time but remained critical to life. This collection of slides captured by Hugh Sackett helps illustrate enduring nature of the tradition and some of its evolutions along the way.

Lefkandi was a protogeometric town found on the coast of the South Euboean Gulf a few hundred meters away from the Lilas River. Lefkandi boasts the Toumba Cemetery, a tumulus containing the remains of a chieftain or hero along with a younger woman, presumably his wife. Both were buried with considerable grave goods which, combined with their luxurious dwelling, places them in a high economic station. Hugh Sackett, along with M. R. Popham, P.G. Calligas, and others, worked to excavate the Toumba Cemetery from 1981-1986. It is unclear whether or not the Toumba Cemetery can truly be called a heroon (shrine for the cult worship of heroes), but there is evidence that, following the construction of the tumulus, more people began to be buried in the Toumba Cemetery, including several other warriors (Thomas et al. 106). Although there exists no evidence of consistent cult worship, an increased interest in being buried closer to the tomb suggests an attractiveness to occupying the same burial space as a great warrior. This may reflect the understanding that Greeks had about the chthonic qualities of hero-power and could be a precursor to the hero cults that would spring up in the 8th and 7th centuries.

The Athenian Treasury at Delphi represents a different kind of interest in heroics. Having defeated the Persians at Marathon, the Athenians sought to cement themselves as powerful actors in the Greek world. They achieved this messaging through the depiction of Herakles and Theseus in the metopes of their new treasury in the panhellenic sanctuary of Delphi. Depictions of Theseus had heretofore been limited to that of black figure pottery (as pictured to the left), but at the treasury he has been reinvented to represent an energized and triumphant Athens (Neer 2004). Theseus becomes the new standard-bearer of a freshly democratic Athens while still retaining his position as former king. Theseus then acts as an easy to rally around character that works to unite Athens by bridging the old with the new. Theseus did have a religious cult (Davie 1982), but in his formulation on the treasury he acts primarily as a political message to the entire Greek world that stresses the unity and strength of Athens. Yet, he remains religiously motivated as the entire treasury is a votive to Apollo in thanks for the victory of the Persians.

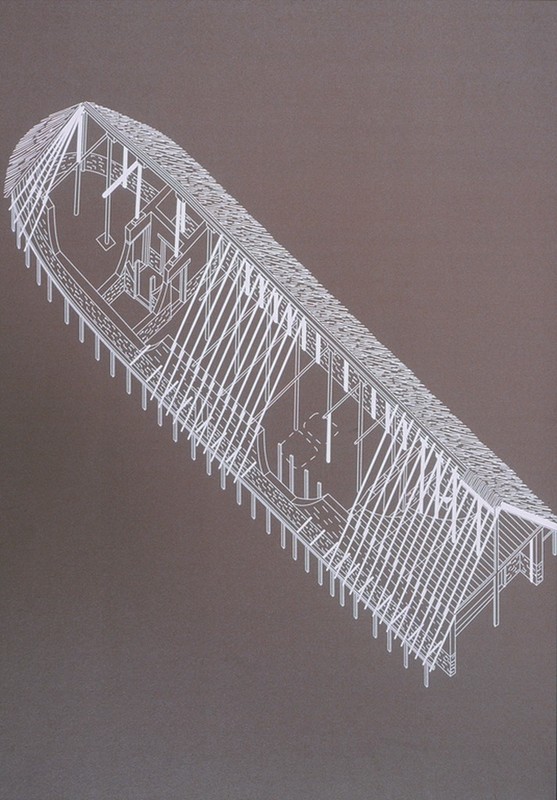

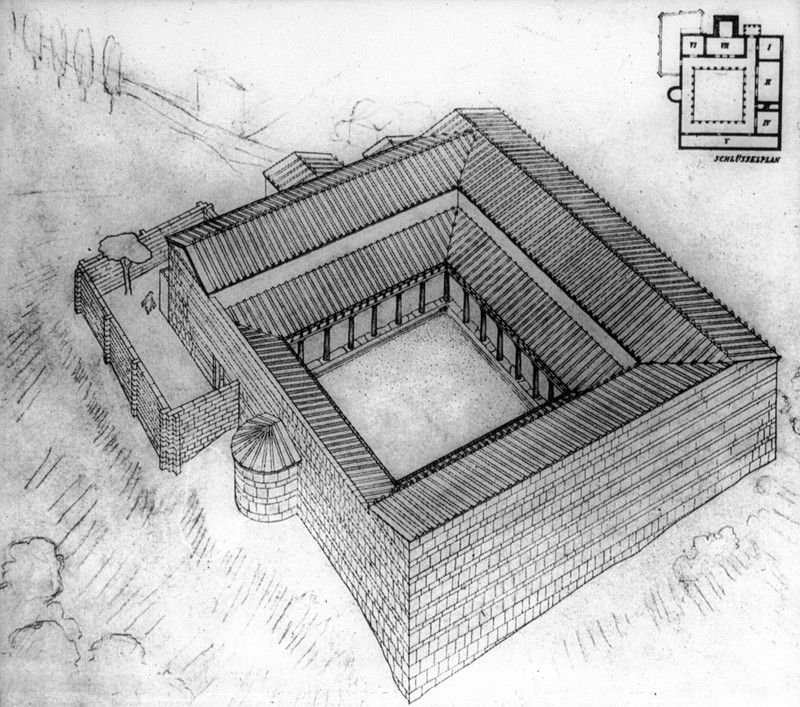

The Heroon of Kalydon (also known as the Leonteion after the hero it entombs) is an almost square building with eight rooms that surround a large peristyle courtyard. Found off the Gulf of Patras in what was Aetolia, it was constructed around 100 BCE during the Hellenistic period and was in use at least until 30 BCE when the Roman emperor Augustus moved the citizens of the city to Nikopolis following its ceremonial founding after the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE (Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites). The heroon continues the chthonic treatment of mortal heroes as the most sacred chamber (the cult room) can only be reached by a staircase that descends into a subterranean room at the end of a vaulted hallway. Within the tomb lay two sarcophagi and an inscription that, when reconstructed, reads “Leon, the new Herakles” (Dyggve et al. 1934). Hellenistic views were more fluid the degree to which the believed in the reality of heroes and their power, but the late construction date for the Heroon at Kalydon reflects the lasting importance of heroes in Greek society. The heroon also reminds of us how local many hero cults were, revolving around tombs in order to stay close to the source of the heroes power – his body at rest in the earth as opposed to ascending to heaven.