Knossos, the Bull and the Myth of the Minotaur

The civilization which inhabited the Palace of Knossos during Bronze Age was the Minoans, who lived on what is now Crete. It was also at one point the most powerful civilization in all of the Aegean region (Hood 2003). And, although there are many palaces on Crete which characterize the Minoan period, Knossos is the largest of all. In fact, the palace flourished during the Late Minoan period, c. 1700-1500 BCE.

Arthur Evan’s excavations of the Palace of Knossos from 1900-1905 led some archaeologists to believe it to be the site of the myth of the Minotaur and King Minos’s labyrinth (MacGillivary 2000). The myth tells the story of King Minos, whose wife is impregnated by a bull and bears the minotaur, a creature with the body of a man and the head of a bull. The myth states that King Minos then built a labyrinth to keep the minotaur inside of. Among the information supporting that the palace is indeed related to this myth is its maze-like layout and the copious bull imagery discovered at the site. Thus, some archeologists agree with Evans: Knossos was King Minos’s labyrinth (Seltman 1953).

However, many 21st-century archaeologists reject the conclusion that Knossos was the site of King Minos’s labyrinth. They argue that the bull motif ought not be used as evidence to justify Knossos as King Minos’s labyrinth because it was a common Minoan symbol and not unique to Knossos (MacGillivary 2000). Minoan art, including cups and rhyta, often featured activities like bull hunting and bull jumping, as the Minoans thought the bull to be a symbol of both strength and man's triumph over nature. Regardless, whether or not Knossos is truly the site of the myth of the minotaur, the bull certainly played an important role in Minoan culture and appears often in the Palace of Knossos.

Knossos

Photo taken by Hugh Sackett

April 1975

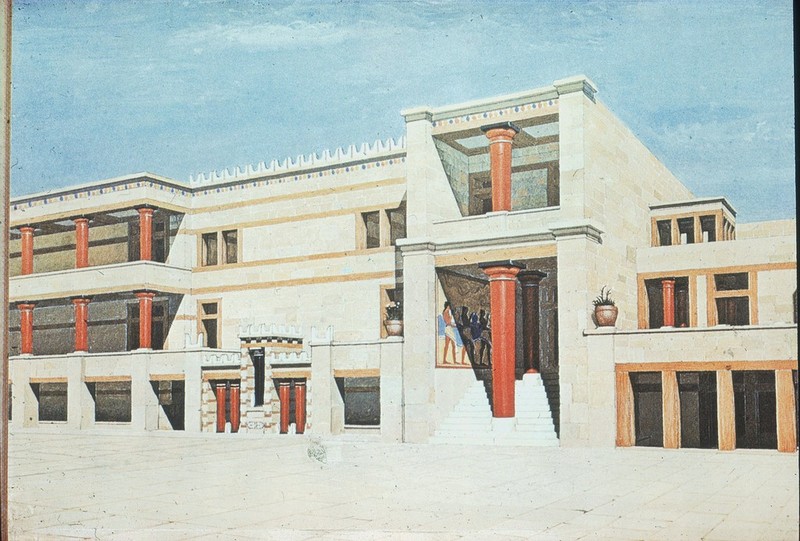

The palace of Knossos is a monumental and imposing structure. It is no surprise that when Evans first excavated the site, he knew he had come across something important. It was built c. 1900 BCE and intentionally destroyed by fire. The Palace was then rebuilt and flourished c. 1700-1500 BCE. It is the largest of all of the Minoan Palaces and covers around 15,000 square meters (Hood 2003).

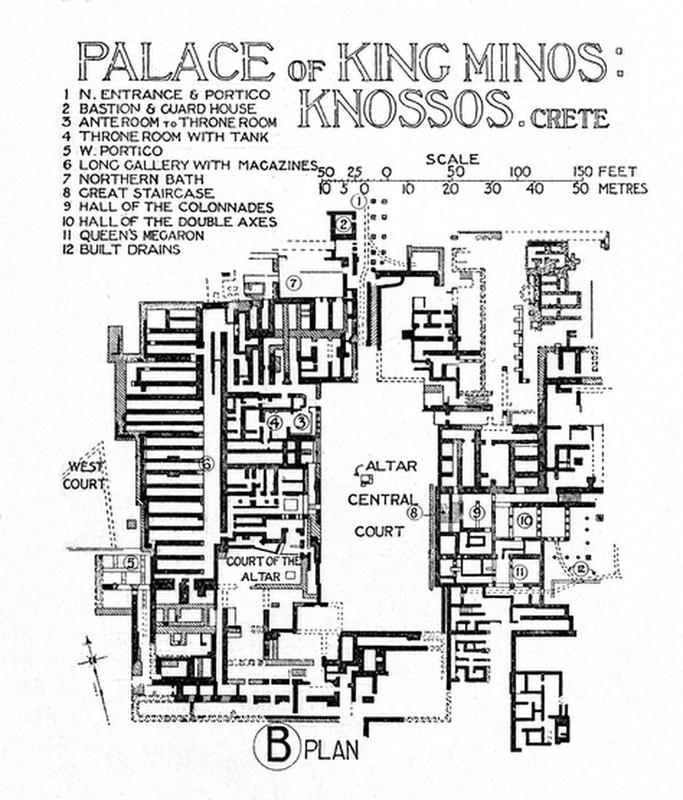

The Palace of Minos at Knossos Plan

Illustration from: Fletcher, Banister. A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method

1921

The Palace of Knossos is roughly square, with an entrance on each side of the palace. The hallways twist and turn, with a large central court. Archeologists, including Evans believe this twisting and turning layout supports the hypothesis that this was the palace of King Minos and the palace which the myth of the minotaur is based on. The meandering halls would have been the labyrinth which housed the minotaur. (MacGillivray 2000)

Image of George Frederic Watts's "The Minotaur"

Photo taken by Hugh Sackett

April 1967

The image taken by Hugh Sackett of George Watts’s “The Minotaur” communicates the draw to the myth of the Minotaur in the late 19th and early 20th century, around the time Evans began his excavations. Watts painted “The Minotaur” in 1885, fifteen years before Evans even began his excavations at Knossos. According to the myth, King Minos demanded a tribute from Athens of seven young boys and seven maidens to feed the minotaur(Seltman 1953). Watts uses the minotaur allegorically to represent man’s lust as commentary against child prostitution in Britain on the late 19th century. (Atkins 2013)

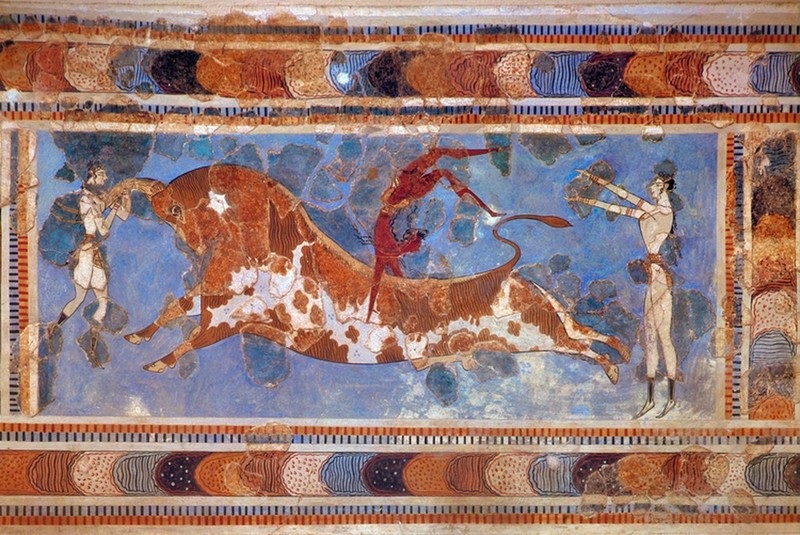

Bull Leaping Fresco

Palace of Knossos, Crete

c. 1700-1500 BCE

The Bull Leaping Fresco from Knossos is arguably the most famous fresco from the site. Similar depictions of people jumping over bulls appears throughout Minoan art, in fresco and sculpture. These sorts of scenes even appear in Egypt.(Younger 1976) Some modern day scholars believe that Minoans never actually jumped over bulls as a sport. They believe that the scene is an allegorical representation of man’s power over a beast. The most controversial recent interpretation argues that this represents a constellation rather than any sort of human activity. (MacGillivary 2000)

Knossos '60 Bull Fresco

Photo taken by High Sackett

1960

Also referred to as the “charging bull”, this fresco appears on the north entrance of the palace of Knossos. Scholars believe that there was a similar fresco on the first palace, which was destroyed c. 1750 BCE, and rebuilt in the new palace. By showing the bull as it charges, this particular depiction displays the power of the bull, which is a common theme in Minoan art.(Woodward 1972) The choice to place this bull at the north entrance of the palace also communicates the power of the palace as an institution as well as the people within it.

Palace of Minos III, Bull

Photo by Hugh Sackett

April 1975

Sackett photographed a crystal plaque from Arthur Evans original excavations records of which bears just the head and shoulders of a bull. Though the rest of the bull’s body no longer exists, he was most likely in a position called the flying gallop, with his back arched almost and its hooves extended to the front and back, as if it was striding in midair. This position is physically impossible for a bull. Oftentimes bulls were depicted in the flying gallop in bull leaping scenes. It is possible that the rest of the scene depicted bull leaping. (Younger 1976)

Rhyton of a Bull

Palace of Knossos Crete

c. 1700-1400 BCE

A rhyton is a vessel with an opening at the top and a small opening at the bottom used for communal libations and celebrations. Someone would carry the object and plug the small opening at the bottom and remove their finger to allow a person to drink from it.(Warren 2008) It was found at the little palace at Knossos. (Logiadou-Plantonos 1979) The Horns are gilded in gold and an object like this was only used by the elite ruling class. The choice to form the object into the head of a bull represents the importance of the bull in Minoan civilization.