About Shelby Foote

Shelby Dade Foote, Jr. (1916-2005)

Life of a Novelist-Historian and

Civil War Celebrity

by Madeleine McGrady

First aired in September 1990, Ken Burns’s acclaimed PBS documentary, The Civil War, introduced millions of viewers to southern writer Shelby Foote. Although he had previously published several novels and a massive three-volume narrative of the American Civil War, Foote enjoyed relatively little popular recognition until his television debut. Appearing on screen with his mellifluous drawl and grandfatherly anecdotes, Foote easily captivated his mass audience, becoming “the presiding spirit of the documentary” and an overnight celebrity.[1] Foote’s interpretation of the Civil War resonated with Americans of all regions and profoundly impacted popular memory of the Civil War in the late twentieth century.

Mississippi Childhood

Born Shelby Dade Foote, Jr. in Greenville, Mississippi, in 1916, Foote moved a number of times during his early childhood as his father advanced within the ranks of the Chicago-based Armour Meats and Company. After his father’s sudden death in 1922, the young Foote and his mother, Lillian Rosenstock Foote, returned to Greenville to live with their Rosenstock relatives. There in Greenville, Lillian Foote worked as a secretary and scraped together a living for herself and her son while they lived in her sister’s house. Regardless of his family’s actual financial situation, Foote later remarked, “I was given clearly to understand as a child that I was a Southern aristocrat.”[2] He was, after all, the grandson of two southern planters, both of whom, in Delta fashion, had touched and lost a fortune in their lifetimes. But as Foote matured and struggled to come to terms with his reality, he began to imagine himself as stranded on the fringes of the southern aristocracy, fighting for wealth and respectability. This self-perception would later influence his works, allowing Foote to sympathize with the poor and marginalized and to critically evaluate the socioeconomic and racial hierarchies of his society.

Another guiding force for Foote and his literary development was lawyer, planter, and famed memoirist William Alexander Percy, who promoted the fine arts in Greenville and regularly hosted prominent writers traveling through the area. In 1931, Foote found himself under Will Percy’s direct influence when the latter’s three young, newly fatherless cousins arrived in Greenville. Upon Will Percy’s suggestion, the fourteen-year-old Foote quickly befriended the three Percy brothers, beginning his celebrated lifelong friendship with fellow author Walker Percy. Foote also gained entry into the Percy house – the cultural headquarters of Greenville – where Will Percy introduced the teenager to classical music and twentieth-century literature. In his adolescence, Foote avidly read Marcel Proust, James Joyce, and William Faulkner, among other modern greats. Such early introductions to literature inspired Foote’s own writing career.

Foote also gained entry into the Percy house – the cultural headquarters of Greenville – where Will Percy introduced the teenager to classical music and twentieth-century literature.

Foote and the Percy brothers attended Greenville High School in the 1930s. There, both Foote and Walker Percy revealed their literary pretensions and contributed to the nationally-ranked school newspaper, The Pica. Following Walker Percy to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Foote enrolled in the fall of 1937. Although he excelled in the classes he enjoyed – mostly history and English classes – Foote’s overall academic transcript revealed that he spent most of his time in the library reading for pleasure rather than studying for class. Foote the aspiring author also dedicated a lot of his time and ink to writing short stories and book reviews for the university’s acclaimed literary journal, Carolina Magazine. After only two full academic years at UNC, Foote felt qualified to begin his writing career in earnest. In June 1937, Foote returned home to Greenville, the source of inspiration for his first novel.

World War II and the Start of a Career

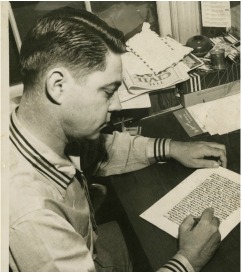

Back in Greenville and determined to write, Foote worked a series of odd jobs before Hodding Carter II, newspaper editor of the local Delta Star, offered him a position as a copy editor. Foote accepted, but only half-heartedly fulfilled his newspaper duties. Instead, he channeled most of his energy into the draft of his first written novel, Tournament, which explored the fictionalized life and decline of Foote’s own paternal grandfather. Decidedly marked by Faulknerian overtones (in fact, Foote had first met his literary hero in June 1938), the novel takes place in Jordan County, modeled after Foote’s own Washington County and the locale of several subsequent works. An editor at Alfred A. Knopf praised the draft’s potential, but ultimately advised Foote to revise it and store it away until he had published other works.

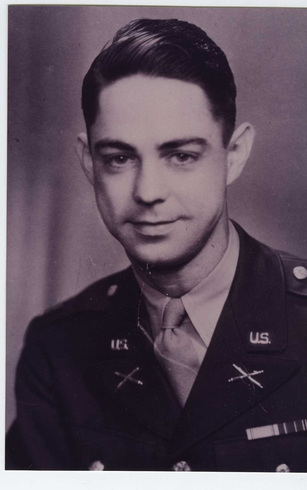

World War II prevented Foote from brooding over this qualified rejection. In October 1939, Foote had enlisted in the Mississippi National Guard and in November of the following year, his “Dixie” Division was called into federal service. Although Foote distinguished himself in training camp and earned a promotion to captain, he was eventually court-martialed and dismissed from service while at base in Northern Ireland in 1944. He received this “Other than Honorable” discharge after driving a company Jeep just beyond the fifty-mile distance limit to visit his future first wife, Tess Lavery of Belfast. Months later, after Foote’s brief enlistment in the Marine Corps and the war’s end, the newlyweds settled in Greenville where Foote worked at a local radio station and enjoyed his first successes as a writer. In 1946 and 1947, the Saturday Evening Post published two of his short stories, prompting Foote to quit his job at the radio station in order to write full time. Recently divorced from Tess Lavery, Foote locked himself away in his Greenville residence and developed his regimented writing routine, producing four published novels between 1949 and 1952.

Against the previous advice of Knopf, Foote took Tournament to press first – publishing house Dial Press distributed the debut novel in 1949. Undeterred by the novel’s mediocre critical reception and poor sales, Foote released Follow Me Down – a Jordan County adaptation of a 1941 Greenville murder trial – the following year. Foote’s third novel based in Jordan County, Love in a Dry Season (1952), garnered the best reviews of the three works.

Fascinated by war and frustrated by his own lack of battle experience, Foote turned somewhat naturally to Civil War fiction; after all, his own paternal great-grandfather had led the 1st Mississippi Cavalry into the 1862 Battle of Shiloh.

But the 1952 publication of Shiloh – in time for the battle’s ninetieth anniversary – marked the height of Foote’s fiction career both in terms of sales and reviews. Fascinated by war and frustrated by his own lack of battle experience, Foote turned somewhat naturally to Civil War fiction; after all, his own paternal great-grandfather had led the 1st Mississippi Cavalry into the 1862 Battle of Shiloh.

Alternating the chapters between the fictional voices of Confederate and Union soldiers, Foote vividly presented the bloody campaign and introduced themes that would later mark his Narrative and the Burns’s series. For instance, Foote casually omitted any reference to slavery or even to the political climate of the divided nation. Instead, he framed the war as a struggle between courageous, ideologically aligned brothers, tragically doomed to largescale fratricide. Revealing his deep admiration for Nathan Bedford Forrest, moreover, Foote presented the controversial Confederate lieutenant general as the hero of the novel, proactive in his battle tactics and fearless in action. Foote’s understanding of the war in Shiloh proved popular with both readers and critics, selling more than six thousand copies in its first few months on the shelf and even earning the praise of William Faulkner.

Success as a Writer

Foote’s first period of professional success coincided with his brief and tumultuous marriage to Memphis socialite Peggy Stinson and the birth of their daughter, Margaret Dade Foote, in 1949. After their 1953 divorce, Foote followed Peggy back to her native Memphis, Tennessee, in order to be closer to his daughter.

From the Bluff City in 1954, Foote published Jordan County: A Landscape in Narrative, a compilation of short stories, and began outlining what he vainly hoped would become his magnum opus, Two Gates to the City. But Foote put his fiction career on hold when later that same year, Random House approached the author of Shiloh to write a 200,000-word history of the Civil War in time for the conflict’s centennial. Foote gladly accepted – and greatly expanded – the proposal. There in his downtown Memphis apartment, Foote commenced work on his famed twenty-year, one-and-half million-word project – The Civil War: A Narrative.

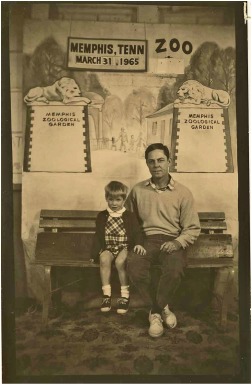

The Memphis apartment would not remain a bachelor’s pad for long. In 1956, Foote married Gwyn Rainer Shea, forming a union that lasted nearly fifty years and produced one son, Huger Lee Foote II, in 1963. While he enjoyed the beginning of a stable home life, Foote published the first volume of the Narrative, Fort Sumter to Perrysville, in 1958, using the stipends from three consecutive Guggenheim fellowships to travel to different battlegrounds for his research. Without delay – and, notably, always without the aid of a research assistant – Foote penned the second volume, Fredericksburg to Meridian, which hit the shelves in 1963. In between the publication of the second and third volumes, Foote took time off from the trilogy and served as the writer-in-residence for University of Virginia in 1963-64 and Memphis State University in 1966-67, adapted Jordan County for the stage as a Ford Foundation fellow in Washington D.C., and taught for part of 1968 at Hollins College. Clearly, Foote enjoyed attention among academic circles for his work. Even more professional recognition would follow after the 1974 publication of the Narrative’s final and longest volume, Red River to Appomattox.

Vital to understanding his trilogy and its critical responses, Foote subtitled the trilogy A Narrative. From the first volume’s cover, then, Foote the fiction author – who, after all, never earned a college degree and never trained as a professional historian – indicated his particular approach to writing history. Explaining this approach in the bibliographical note at the end of the Narrative’s first volume, Foote wrote that by “accepting the historian’s standards without his paraphernalia, I have employed the novelist’s methods without his license.”[3] In practice, this meant that Foote attempted to write about the Civil War as the officers and soldiers who lived through it had experienced it, and not through the critical lens of the historian. Along this line, Foote boldly rejected footnotes in his Narrative, claiming that they would “detract from the book’s narrative quality;” this decision agitated many academic historians.[4] Moreover, Foote shunned original research and only referenced published biographies of military leaders and the 128-volume compilation of military reports and correspondence from the war, Official Records of the War of the Rebellion. Throughout his three volumes, then, Foote offered a chiefly military history of the war, describing the battle tactics and landscapes in vivid detail, delving into the characters and quirks of the major military leaders, and largely neglecting to analyze the causes and consequences of the nation’s bloodiest conflict.

Unsurprisingly, this lack of analysis attracted the criticism of professional historians. C. Vann Woodward, for instance, labeled the trilogy a “purely military history” and though he also praised Foote’s style, literary critic Louis Rubin concluded that Foote had written “a disenthralled narrative of just how the war as fought out.”[5] But these criticisms cannot be evaluated in a vacuum. After all, as Foote scribbled away, twenty years had passed and two revolutions unfolded. The first revolution – the advent of social history – stirred the academic community from the late 1950s through the 1970s, prompting historians to study the lives and contributions of the working class, African Americans, women, and other previously voiceless sectors of society. This professional trend did not influence the self-proclaimed “novelist-historian,” who remained intent on retelling the story of military elites while largely ignoring the war’s social and political contexts. Coinciding with this popularization of social history in academic circles, the civil rights movement rocked the entire nation at mid-century. Again, this revolution hardly influenced Foote’s Narrative. Although he generally sympathized with the plight of African Americans and opposed segregation as early as the 1930s, Foote rarely acted on these beliefs. Moreover, he wrote his trilogy from an identifiable white southern perspective. As in Shiloh, this perspective manifested throughout the Narrative in near silence over slavery and black contributions to the war effort. Instead, Foote emphasized the close relationships between the opposing commanders and generally presented the Civil War as a white man’s war – a brother’s war – fought between two noble adversaries. Criticism of this interpretation would later resurface with greater force in response to Foote’s appearances in the Burns documentary.

To his credit, Foote paid greater attention to the Western theater – the fighting outside of the well-known Virginia battles – than had other Civil War writers, including contemporary midwestern historians Bruce Catton and Alan Nevins. Literary critics also appreciated Foote’s narrative style. Among other warm reviews, Peter Prescott claimed in Newsweek that to read Foote’s “chronicle is an awesome and moving experience. History and literature are rarely so thoroughly combined as here; one finishes this volume convinced that no one need undertake this particular enterprise again.”[6] The public largely agreed and the Narrative sold well, earning Foote nearly $100,000 in royalties within the first several months of the trilogy’s completion.

With the Narrative now behind him, Foote resumed his fiction career, releasing September, September in 1977. Set in 1957 Memphis, Foote’s fifth and final novel revolved around the kidnapping of a wealthy black family’s son by white criminals. Exploring the racial and political climate of the 1950s south, September, September marked Foote’s first attempt to capture black life and culture. Although it received little critical praise and sold slowly, Turner Broadcasting Service adapted the novel into the 1990 movie Memphis, starring Cybill Shepherd. Otherwise, however, the late 1970s and the 1980s beheld little creative output for Foote. Once again, Foote had turned to Two Gates to the City, the elusive novel now thirty years unfinished. And once again, his unwritten masterpiece defeated Foote, who eventually abandoned the project. Not only did his writing stagnate during the 1980s, but Foote also suffered from health problems. In 1983, the 67-year-old underwent an angioplasty and in 1985 into 1986, he was treated for prostate cancer.

Ken Burns and National Recognition

Foote had regained his health before filmmaker Ken Burns first interviewed him in April 1986. At the time, Burns was working on his landmark PBS Civil War television documentary, which first aired four years later in September 1990. Combining historical photographs, period music, celebrity narration of primary source documents, and historians’ analyses, Burns presented his interpretation of the Civil War to a massive audience of thirty-nine million viewers. Thanks to Robert Penn Warren’s recommendation, Foote served as a consultant and talking head for Burns’s project, along with such prominent historians as Barbara Fields, Ed Bearss, and Stephen B. Oates. Nevertheless, Foote’s interpretation of the war came to dominate the documentary. After all, Foote made a total of eighty-nine appearances in the nine-episode documentary – far more than any other expert – and offered nearly one hour of anecdotal history in his Mississippi drawl. Just as he wrote in his Narrative, Foote on screen spoke of the Civil War as a sentimental military struggle between ideologically aligned white brothers, emphasizing the battle prowess and valor of certain generals, including his controversial hero, Nathan Bedford Forrest. Burns largely followed Foote’s interpretation.

Like Foote’s Narrative, Burns’s documentary attracted a flood of criticism from the historical academy. According to Eric Foner, for instance, Burns offered “a vision of the Civil War as a family quarrel among whites, whose fundamental accomplishment was the preservation of the Union and in which the destruction of slavery was a side issue and African Americans little more than a problem confronting white society.”[7] Catherine Clinton, historian of American women, agreed, arguing that the final “images of a re-enactment of Pickett’s Charge in 1913 sentimentalized the theme of reconciliation, providing a folksy and comfortable closure for white Americans – and a racialized distortion of the war’s meaning.”[8] In short, historians recognized and resented Burns’s – and thus Foote’s – fratricidal thesis as a means to avoid the issue of slavery and its connection to the Civil War.

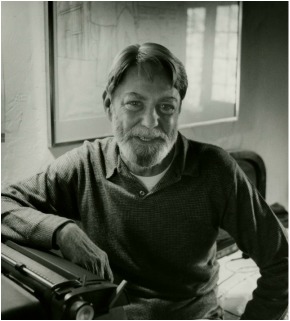

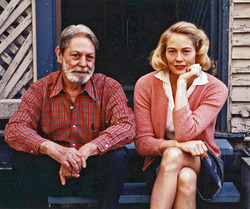

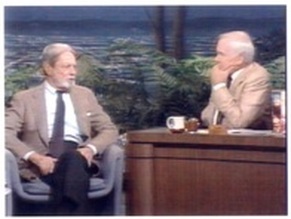

The mainstream viewing public, on the other hand, embraced the Foote-Burns interpretation of the war as they embraced Foote himself. The bearded, charming, and knowledgeable Foote, as People magazine put it, represented “a kind of video folk hero” to Burns’s audience.[9] Moreover, Americans of all regions agreed with southern novelist Reynolds Price, who claimed that Foote was “the last of the Southern gentlemen. In the best sense of the word, he’s a man of grace and courtesy.”[10] Foote’s appeal was so strong that, in fact, for a period after the documentary’s PBS debut, he received about twenty phone calls a day from adoring fans seeking answers to their historical questions. In addition to People, USA Today and Newsweek also profiled Foote, and he even appeared on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson in November 1990. In effect, the Burns series turned Foote into a Civil War celebrity.

After decades of scribbling in the shadows of popular acclaim, Foote finally received widespread recognition for his written works. In the 1990s, his book sales skyrocketed, he accepted twenty honorary degrees from colleges and universities across the nation, and he was asked to write introductions for several important works. Foote also became a public defender of Civil War history, protesting the development of a Disney theme park on the battlefield of Manassas and defending the statue of his hero, Nathan Bedford Forrest, in a public Memphis park. Inundated with phone calls from fans and readers and now saddled with public obligations, Foote’s own writing career effectively ended after the Burns series. At the time of his 2005 death in Memphis, Foote was one of the most well-known and celebrated Civil War writers.

Footnotes

[1] Ken Burns qtd. in Susan Howard, “The Civil War Expert Finds Similarities with Today’s Conflicts,” New York Newsday, January 24, 1991, 75.

[2] Shelby Foote qtd. in Tony Horwitz, Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War (New York: Pantheon, 1998), 149.

[3] Shelby Foote, The Civil War: A Narrative, Volume One (New York: Random House Inc., 1958), 815.

[4] Ibid.

[5] C. Vann Woodward, “The Great American Butchery,” The New York Review of Books, 6 March 1975: 12; Louis Rubin, “Old-Style History,” The New Republic, 30 November 1974: 44.

[6] Peter S. Prescott, “Where the Action Was,” Newsweek, 2 December 1974: 103.

[7] Eric Foner, “Ken Burns and the Romance of Reunion,” in Ken Burns’s The Civil War: Historians Respond, ed. Robert B. Toplin (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 101-118.

[8] Catherine Clinton, “Noble Women As Well,” Ken Burns’s The Civil War: Historians Respond, d. Robert B. Toplin (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 63-80.

[9] Michelle Green and David Hutchings, “The Civil War Finds a Homer in Writer Shelby Foote,” People, October 15, 1990, accessed December 3, 2015, http://www.people.com/people/archive/article/0,,20113329,00.html.

[10] Reynolds Price qtd . in Stuart Chapman, Shelby Foote: A Writer’s Life (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2003), 257.