Foote's Jewish Background

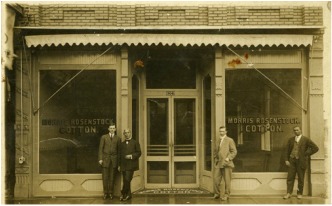

Shelby Foote’s Jewish ancestry came from his maternal grandfather Morris Rosenstock, a Viennese Jew who emigrated to the United States in the 1880’s.[1] In the relatively cosmopolitan Greenville, Mississippi, Jews were broadly accepted in the town’s social and cultural circles, and Foote and his mother did not face anti-Semitism there. In fact, Foote even claimed that there were more Jewish members of the Greenville Country Club than Baptists.[2] Although he attended synagogue every week with his mother until age eleven, Foote never developed a strong Jewish identity. Nevertheless, he understood from a young age that his Jewish ancestry could be problematic in his future.[3]

Foote’s suspicions were confirmed at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity, whose members included Foote’s close friends Walker and Roy Percy, rejected him because of his Jewish background. Although the Alpha Tau Omega fraternity initially accepted him, the brothers ostracized Foote once they learned of his Jewish ancestry and later expelled him from the fraternity.[4] This firsthand experience with discrimination possibly contributed to Foote’s comparatively progressive stances against racial segregation.[5]

In order to avoid similar experiences, Foote’s paternal grandmother urged him to become an Episcopalian, and when he was in his twenties, Foote was baptized and confirmed in the Episcopal Church.[6] But Foote did not develop a strong Christian identity either, and struggled to accept certain Christian doctrines. For example, Foote’s service in the Army and his later interest in the American Civil War contradicted Christian pacifism and “turning the other cheek”, and Foote himself noted his tendency to “buck back, particularly when any authority leans on me.”[7] Furthermore, Foote did not hesitate to share his skepticism of religion with those around him. He openly criticized Walker Percy’s conversion to Catholicism, and believed that his friend’s “religion and moralizing tendencies were threatening to interfere with his development as an artist.”[8] In short, although Foote’s Jewish ancestry did not contribute to any religious identity, it allowed Foote to sympathize with other minority groups facing discrimination.

Footnotes

[1] Tony Horwitz, “At the Foote of the Master,” in Confederates in the Attic (New York: Pantheon, 1998), 148.

[2] Jon Meacham, “An American Master,” in American Homer: Reflections on Shelby Foote and His Classic ‘The Civil War: A Narrative’ (New York: Modern Library, 2011), 4.

[3] Horwitz, “At the Foote,” 148.

[4] Jay Tolson, “Art, War, and Shelby Foote,” in American Homer: Reflections on Shelby Foote and His Classic ‘The Civil War: A Narrative’ (New York: Modern Library, 2011), 24.

[5] Ibid., 24.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Horwitz, “At the Foote,” 148.

[8] Shelby Foote and Walker Percy, The Correspondence of Shelby Foote and Walker Percy, ed. Jay Tolson (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1998).