Minoan Frescoes: Conservation Techniques and Compositions

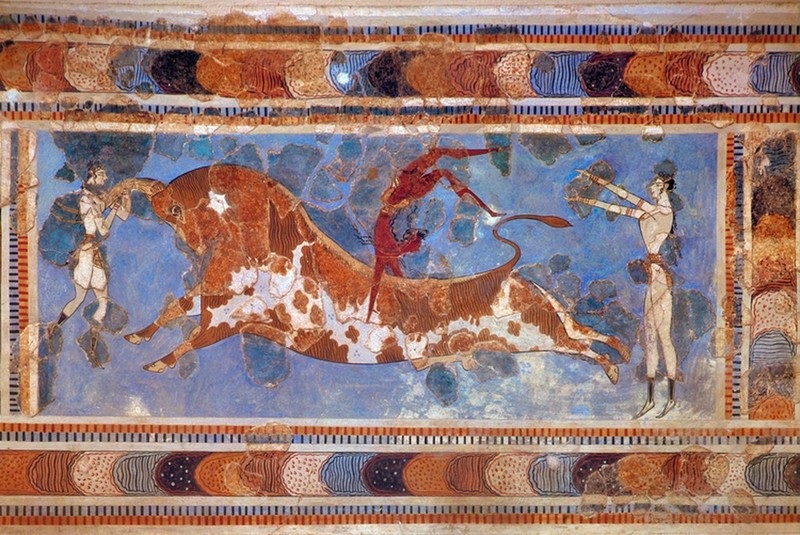

Discovered over a century ago, the Bull-Leaping Fresco has been extensively studied and theorized about by many art historians and archeologists. It allows us to glean information on the way frescoes were made, along with the techniques used on frescoes and wall art captured by Hugh Sackett, this being conservational or original work.

Known to be made of plaster and originally thought as archaic Greek due to their excavation from prehistoric floors (Shaw 174), the Bull-Leaping Fresco is also telling of the techniques used by the artist. According to Maria C. Shaw, when studying the bulls and leapers of Fresco No. 5, "given the superposition of several pigments... [and the fact that] they still adhere to the successive painted surfaces relatively well... suggests that the artist was working at some speed" (Shaw 175). Speed which, contrasted by the discovered traces of an ochre yellow outline, becomes a contradictory practice. Frescoes naturally require speed from the artist since it is a technique that uses a wet surface and wet paint. However, the ochre yellow tracings demonstrate another kind of artistic inclination, one towards calm and a steady pace. The underlying outline demonstrates the artist attention to detail, towards a meticulous process which precisely takes care of compositional errors and involes planning out the entire compositional drawing of the fresco. This is of course for the original technique used to make the fresco.

On the other hand, archeologists and art historians had the job to assemble the pieces and fill in the gaps of what was left behind at the Palace of Knossos. Reconstructions and conservation efforts like this will be furthered discussed in the following pieces photographed by Sackett.

To continue on the analysis of bull frescoes, relief frescoes were common when treating this significant symbol in Minoan frescoes. Moreover, this specific relief fresco is noted by Sackett as a reconstruction, over a reconstructed porch. And it is recognized as so by many modern scholars as well. In fact, the bull-relief photographed by Sackett, is known as the charging bull fresco of the Knossos North Entrance. It is also noted by scholars, the significance of said reconstruction, not only to preserve and revive an ancient site, but for the actual purposes of studying it in the scholarly practie. Scholars say, "except for the rebuilt portico containing the relief fresco of the charging bull" ... there is "no very good plans of the whole area" (Woodard, pg.113). The lack of good study plans of the Palace of Knossos is commented by various scholars and demonstrate the importance of reconstruction and restoration in archeological sites.

Located at the Palace of Minos in the room known as the Queen's Megaron, the Dolphin Fresco lays overhead the double-door frame. As some sources specify, this pleasant wall painting was the reconstruction of the original work. It is important to mention that the original remains of the fresco are on display and restored in the Heraklion Museum but here are some notable differences. Opposed to the reconstruction inside the Palace, the restoration in the Museum only features two of the dolphins and 13 smaller fish (Koehl, pg.407). This again, helping the viewer understand the difference between restoration and reconstruction, important in the study of art history, here through the lenses of Hugh Sackett.

The "Ladies in Blue" Fresco was first excavated before 1914 near Royal Magazines in Knossos. The composition depicts three women that although could be argued Minoan due to their open-chest garments and traditional colors used, debates arise when there is restoration involved. On an article published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, it was argued by the writer Evelyn Waugh, that by looking at this fresco "it is not easy to judge the merits of Minoan painting". The writer makes this argument due to the presence of virtually minimal original fresco after extensive restoration done by Emile Guillieron. More when the restorations are something so fitting to today's aesthetic standards standards. And just how Waugh mentions seemingly an "inappropriate prediliction for the covers of Vogue".

Here I want to highlight the restoration techniques used to preserve frescoes which both, art historians and archeologists ought to keep in mind when dealing with excavated material such as that photographed by Hugh Sackett.

Conservational studies here give archeological findings an interesting spin. By conservational chemical analysis, scholars have been able to identify details which help further understand the gaps created in restored work, and why writers such as Waugh, think that heavily restored works lose their merits to be judged and considered part of scholarly material.

Scholars mention that in the scientific analysis of Minoan Frescoes at Knossos, samples of pigments were taken, and two types of blue were found incorporated in the frescoes. The mentioned colors were first a sky-blue color consisting of small blue crystals. The pigment had "a high copper content and was identified as Egyptian blue" (Cameron, Jones, Philippakis, pg. 140). On the other hand, the second color had large dark blue crystals that correlate with the presence of a high concentration of iron identified as riebeckite. Frescoes had fluctuating concentrations of both types of blue which eventually made the frecoes distinct in composition compared to their seemingly equal restoration pieces.

This detail however, demonstrates the importance of conservation practices that come with the analysis of the ancient colors. Detail that in itself cannot be left out of the studies of the techniques used in the conservation efforts of Minoan frescoes.

Finally, an examination of conservation practices on minoan frescoes could not be complete without the mention of Sir Arthur Evans and his reconstructions made of the throne room and the South Entrance of the Palace (Hopkins pg. 416). Or those of Mark Cameron on the Cup bearer frescoes (Hood, pg.45). Both scholars made a huge contribution to the conservation and restoration practices thanks to which we are today allowed to study the splendid Minoan frescoes.

Bibliography

-

Cameron, M. A. S., R. E. Jones, and S. E. Philippakis. “Scientific Analyses of Minoan Fresco Samples from Knossos.” The Annual of the British School at Athens 72 (1977): 121–84. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30103383.

-

Hood, Sinclair. “Dating the Knossos Frescoes.” British School at Athens Studies 13 (2005): 45–81. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40960393.

-

Hopkins, Clark. “A Review of the Throne Room at Cnossos.” American Journal of Archaeology 67, no. 4 (1963): 416–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/501626.

-

Koehl, Robert B. “A Marinescape Floor from the Palace at Knossos.” American Journal of Archaeology 90, no. 4 (1986): 407–17. https://doi.org/10.2307/506025.

-

Profi, S., L. Weier, and S. E. Filippakis. “X-Ray Analysis of Greek Bronze Age Pigments from Knossos.” Studies in Conservation 21, no. 1 (1976): 34–39. https://doi.org/10.2307/1505608.

-

Shaw, Maria C. “The Bull-Leaping Fresco from below the Ramp House at Mycenae: A Study in Iconography and Artistic Transmission.” The Annual of the British School at Athens 91 (1996): 167–90. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30102546.

- The MET Fifth Avenue. "Reproduction of the "Ladies in Blue" fresco." Emile Gillieron, metmuseum.org, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/258137

- Woodard, William S. “The North Entrance at Knossos.” American Journal of Archaeology 76, no. 2 (1972): 113–25. https://doi.org/10.2307/503855.